ETFs and ETCs

on BUX

ETFs are baskets of assets that allow you to spread little sums over up to thousands of different underlying securities at a very low cost, enabling you to build a diversified portfolio quickly, easily, and conveniently. ETCs, on the other hand, offer exposure to a range of commodities such as gold, silver, and platinum, providing an additional asset class to diversify your portfolio.

What is

an ETF?

ETF stands for exchange-traded fund. As its full name suggests, an ETF is an investment fund whose shares can be traded on an exchange.

As you may know, an investment fund is an institution that collects money from investors to buy assets that will generate a return if their value increases. By investing high amounts of money, an investment fund is able to keep transaction costs low thanks to economies of scale.

The second main feature of an ETF is that you can trade it on an exchange. Pretty much like listed companies, exchange-traded funds divide their ownership into shares that can be bought and sold on exchanges by placing an order at a broker like BUX.

This feature distinguishes them from other investment funds like mutual funds, making ETFs generally more liquid, which means that you can buy or sell your stake in an ETF more quickly, easily, and securely at any time during market hours.

Usually, an ETF invests in a basket of assets from the same class, often by passively replicating an index.

ETFs can invest in any asset class: stocks, bonds, commodities, currencies … you name it. Despite not directly owning the underlying securities, when investing in an ETF you become entitled to receive all the income they generate, be it dividends or interest payments.

Usually, an ETF invests in a basket of assets from the same class, often by passively replicating an index — e.g. the FTSE 100. In that case, fund-management costs will be very low, because the process is highly automatable. Index-tracking ETFs show therefore very low fees compared to actively managed funds, which makes them a great instrument to diversify your investments quickly, easily and cheaply.

How does an ETF work?

An ETF is a basket of assets (stocks, bonds, currencies …) whose ownership is divided into shares that are bought and sold by investors on an exchange.

Its value (called Net Asset Value, or NAV) is equal to the total value of the assets it owns, and it changes constantly with their price. At the same time though, since shares of the ETF are traded on the market themselves, their price will be determined by the interaction between demand and offer for the ETF, not by the value of its underlying assets.

So how can you be sure that the price of an ETF — say, one replicating the S&P 500 index — will track the value of the underlying basket without deviating too much from it?

That is ensured by a continuous mechanism of creation and redemption of ETF shares that involves two different players: the issuer of the fund, also called sponsor or fund manager, and a group of large institutional investors called “authorized participants”, who are often market makers.

It works like this:

Every day, the issuer publishes the list of securities that the fund needs to own together with the relative weights they need to have in order to replicate the index it is tracking. This is called a “creation basket”.

Once they have this information, authorised participants collect the stocks listed in the creation basket at the required percentages, either by buying them or by drawing them from those they hold in their inventory. They then deliver this basket of stocks to the issuer in exchange for newly created shares of the ETF, which they can sell on the market to individual investors.

This process also works the other way around: authorised participants can also sell ETFs to the issuer in exchange for a corresponding quantity of underlying securities. This is called a “redemption basket”.

Therefore, unlike stocks, ETF shares are not listed through an initial public offering. Instead, they are created and redeemed on a daily basis via this mechanism.

The symbiotic mechanism between issuer and authorised participants ensures that the ETF price doesn’t diverge too much from the portfolio it is tracking.

But why do authorized participants partake in this process? What do they earn from it?

Well, as we said at the beginning, the price of the ETF and that of the underlying basket can differ because they are driven by different forces. When the ETF price rises too much compared to the underlying portfolio, authorized participants can make a profit by buying the underlying assets, exchanging them for new ETFs with the issuer, and selling those ETFs on the market. That increases the price of the underlying portfolio while decreasing the price of the ETF, making them meet again.

This mechanism, called arbitrage, works the other way around as well: when the ETF is undervalued compared to the underlying portfolio, authorized participants can make money by buying the ETF, redeeming it in exchange for the underlying stocks, and selling these on the market.

This symbiotic mechanism between issuer and authorized participants ensures that the ETF price doesn’t diverge too much from the portfolio it is tracking.

Types of ETF

There are many kinds of ETFs, different in terms of investment strategy, asset class, geographical focus and other features. Here we look at the most important ones.

A first basic distinction can be made between active and passive funds.

Active ETFs are actively run by fund managers, who pick the assets they reckon will perform best with the aim of beating a certain benchmark. These funds tend to have higher fees compared to passive ETFs, and research shows that only a minority of them actually manages to beat the market over the long run. They are therefore way less popular than passive ETFs and make up a fraction of the total ETF market.

Passive ETFs instead are funds that passively replicate an index (of any asset class), which is why they are also referred to as index trackers. Since their replication process doesn’t need any human decision making, passive ETFs have lower fund-management costs and therefore lower fees than active funds. That makes them a great instrument to diversify one’s investments easily and cheaply, and is the main driver of their popularity among investors. Since they represent the vast majority of ETFs out there, we’ll focus on them from here on.

Passive ETFs can be categorised by asset class. Here the most common ones:

- Equity ETFs: funds designed to track a particular stock index like the S&P 500 or the DAX. They can be focusing on a specific sector, industry, market cap, geographical area or on other features (dividends, growth …). Therefore, next to ETFs with broad exposure like those tracking the MSCI World index, you’ll find funds investing only in a particular subset of shares like healthcare stocks from Europe for example.

- Fixed-income ETFs: funds built to provide exposure to bonds of any kind. They can track broad bond indices like the Bloomberg Barclays US Aggregate Bond Index or focus on specific types of fixed-income assets like government bonds, corporate bonds (also from a single sector), municipal bonds, or a mix of these. They often invest in assets with a specific maturity — short, mid or long term, a specific credit rating and from a specific geographical area.

- Commodity ETFs: funds that track the price of a commodity (such as gold, oil, or natural gas), or of a basket of commodities. In the case of precious metals, the fund can hold the underlying assets physically by storing them in a vault, while in all other cases it will have to gain exposure to their price variations by buying future contracts.

- Currency ETFs: funds designed to invest in a specific currency or baskets of currencies.

These were the most common types of ETFs you can find on the market. They are more than enough to build well-diversified, long-term portfolios for investors with any kind of risk/reward preferences. However, there are also some other more complex funds providing exposure to more sophisticated strategies.

- Alternatives ETFs: funds designed to allow investors to trade particular strategies (like long/short equity, currency carry or equity market neutral), trade volatility or hedge against inflation.

- Inverse ETFs: funds that enable you to profit from a decline in a certain index or asset.

- Leveraged ETFs: funds that allow you to invest in a basket of assets with leverage.

Pros and cons of ETFs

Compared to other investment tools like mutual funds or stocks, ETFs show several specific perks that are at the basis of their growing popularity among retail investors. On the other hand, they also feature some risks that you should be aware of.

Pros of ETFs:

- Accessibility: the minimum investment can be lower than 10 euros.

- Broad exposure: they provide exposure to tens, hundreds or even thousands of different securities, allowing for a degree of diversification otherwise very expensive to obtain.

- Cost-effectiveness: passive ETFs in particular charge very low fees thanks to low managing costs and economies of scale.

- Simplicity: you can trade them as easily as you trade stocks throughout trading hours with an app like BUX.

- Transparency: ETFs are required to publish their holdings daily, while their market price is constantly updated and made available to the public.

Cons of ETFs:

- Tracking error: although ETFs usually manage to track their underlying index quite well, technical issues or disruptions in the creation and redemption mechanism can generate discrepancies.

- Fund closure risk: if the fund closes, investors can be negatively affected in fiscal terms because the closure could force them to realize gains, creating a tax event for them. Plus, they’ll have to find a new way to invest that money.

- Counterparty risk: depending on their replication mechanism, some funds could bear this kind of risk. ETFs can replicate the underlying index in different ways, the most common ones being full replication, sampling and synthetic replication:

- Full replication: the ETF replicates the index 1:1.

- Sampling: the ETF holds only a selection of the securities in the index.

- Synthetic replication: the ETF replicates the index by using a financial derivative. A fund like this has some level of counterparty risk because it doesn’t own the underlying securities.

- Possible risk of illiquidity: ETFs investing in illiquid instruments, like high-yield corporate bonds or leveraged loans, can become illiquid themselves in times of market stress, turning out difficult to sell timely and at a convenient spread.

How to invest

in ETFs

Let’s say you know what ETFs are, you’ve learned how they work and decided they are the right tool for you to invest in the long run. Now you may be asking yourself where to start. There are so many types of ETFs, that deciding what to choose can be a daunting task. In this section, we will go through the process of building an ETF portfolio step by step, providing you with a guide on how to take the necessary decisions at each stage. Obviously, these decisions are yours to make, but the information here below will help you ask yourself the right questions in the right order.

Before you start

Before we start building a portfolio, we must make sure you understand how returns are tied to risk, and how you can reduce that risk through diversification.

First of all, in any investment, rewards are a function of risk: higher potential returns usually imply a higher chance of losing your money. That’s because the yield of an investment is actually nothing but a way to compensate the investor for risking their capital, so the two things have to go hand in hand.

Securities from the same asset class usually show similar risk and provide on average similar rewards, while different asset classes generally present different risks and rewards. Low-risk investments like government bonds will normally provide lower (but safer) yields than risky assets like stocks, which on average can pay back a higher return over the same period, but are also more likely to bring losses. As we’ll see later, you can define both the risk and the expected returns of your portfolio by combining high-risk and low-risk assets, a process called asset allocation.

Also, notice that risk is not something abstract. It can be estimated in a number of ways, the most common being standard deviation, which measures the extent to which the actual returns of an asset can differ from its expected returns over a given period. The higher the standard deviation, the wider the possible fluctuations. Take for example a stock with a 10% average annual return and a 15% standard deviation: most of the time its returns will fluctuate between 25% (10%+15%) and -5% (10%-15%). Now think of a bond that yields 3.5% a year with a 3% standard deviation. Its returns will vary between 0.5% and 6.5% most of the time. As you can see, the latter is way less risky than the first one, but its expected returns are way lower. You can learn more about standard deviation here.

Diversification helps you achieve the same expected return at a lower risk.

So, as we said, a certain amount of risk is unavoidable if you aim to reach a certain return. But for any given expected return, you don’t want to take any unnecessary risk. If you are to travel from Paris to Rome by motorbike, you can choose to either wear a helmet or not: the expected return will be the same (you expect to get to Rome in the same amount of time), but the latter option will imply a much higher risk of not arriving at all.

When investing, the way to avoid unnecessary risk is by diversifying your investments, i.e. by distributing your capital over a number of different securities related as little as possible. In fact, the higher the number of assets you spread your capital over, the lower your chances of losing everything at once.

Despite this fact being very intuitive — never put all your eggs in one basket, your grandma would say — it’s worth spending a minute to understand why it holds.

Any security is affected by two kinds of risk: a systematic one, affecting all assets of the same class, and a specific one, tied to the single security. An example of systematic risk is the Covid-19 pandemic: when it broke out in early 2020, the whole stock market plummeted. Specific risks are instead tied to the single entity that issued the security: for instance, shares of an oil & gas company extracting hydrocarbons in the Gulf of Mexico will be subject to the risk of hurricanes disrupting the company’s operations. Research shows that specific risk factors account for most of the variation in a stock’s performance.

Now, when you buy one single stock, the return you can expect from it over the long run is the average return historically generated by equity. In exchange for that return, you take on both the specific and systematic risk the stock bears.

If instead you bought a portfolio made up of all the stocks in the world, your expected return over the long run would still be pretty similar to the return of the single share, but you’d only incur the systematic risk, while the specific risks of all the single stocks in the portfolio would tend to average out. In other words, you’d achieve the same expected return at a lower risk.

That’s how diversification works, and ETFs give you the possibility to exploit this mechanism in a fast and cheap way by letting you spread little sums over tens, hundreds, or even thousands of different underlying securities.

Determine your risk tolerance

The first step to build a portfolio is to determine your risk tolerance, a.k.a. the amount of risk you are willing to take. To do that properly, you should speak to a financial advisor or use one of the free tools you can find on the Internet. The process will consist of asking yourself a few questions like: why are you investing? When will you need your money back? What is your individual financial situation?

Why are you investing?

One can invest for many reasons: to retire more comfortably, to send kids to university, to buy a hut in the mountains… the more the future availability of that money is important to you, the less risk you will be willing to take on. Sensible parents, for example, will take less risk on the savings set aside to grant their kids an education than on those to buy a boat when they retire.

When will you need your money back?

As to when you’ll need your money back, i.e. your investment horizon, the longer you can live without that money, the more risk you’ll be able to accept. While a number of variables can affect it, your investment horizon will always be a function of how old you are: the younger you are, the higher the risk you can take because you’ll likely have more time to recover from possible losses.

What is your individual financial situation?

Lastly, and quite obviously, your risk tolerance will be related to your financial condition: people with a higher net worth are simply more able to take losses.

The answers to the questions above will let you understand the maximum level of risk you are comfortable taking, so you can choose an asset allocation that maximises your expected returns, given that level of risk. You’re ready to see your investment lose 40% of its value on a bad year? Then you will choose a certain asset allocation. You don’t feel comfortable risking more than 10% of your capital on each given year? Then you’ll go for a completely different one.

Choose your asset allocation

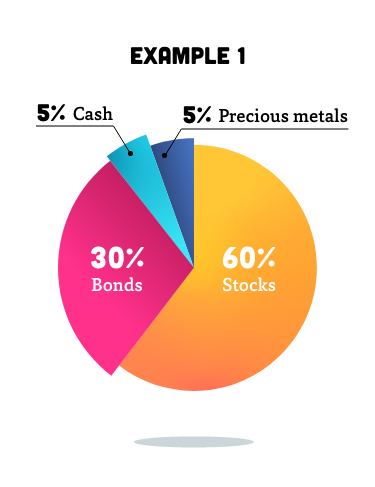

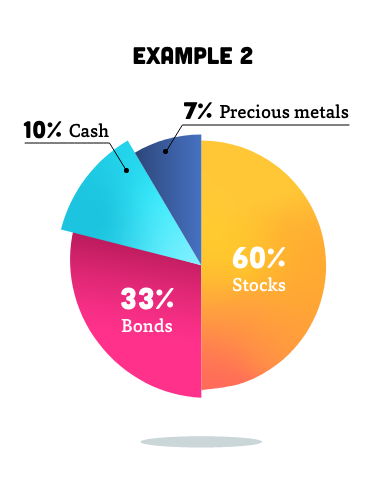

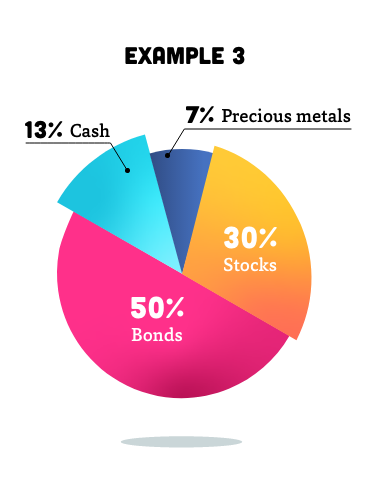

This is the most important choice you’ll make in the process. Asset allocation is the decision of how much capital to invest in each asset category. Usually, a diversified portfolio will include mainly stocks and bonds, to which one can add cash, precious metals, and other assets if need be. Here below you can see three different examples of asset allocation:

By varying the relative amount of stocks, bonds, and other assets in your portfolio, you can increase or decrease its level of risk and expected returns. In fact, the expected return and standard deviation of a portfolio are simply given by the weighted average of the expected return and standard deviation of its assets.

In general, stocks bring high risk and high returns, giving you the highest growth opportunity. Bonds provide instead lower risk and returns, hedging your portfolio during recessions. Cash can be kept to ensure a certain extent of liquidity but it is subject to inflation and bears no returns, while precious metals can be used as safe assets – they don’t provide returns per se but tend to keep their value over time and perform well during turmoil.

Therefore, the more equity you add to your portfolio, the higher your risk and potential returns. Investors with high risk tolerance and long investment horizon will thus allocate a wider share of their capital to stocks, while those with lower risk tolerance or a shorter investment horizon will want to invest more in bonds and other safer assets.

All right, but how do you decide how much money to allocate to each asset class? Well, as said, asset allocation depends on your risk tolerance, but a widely used rule of thumb to start from is to invest in stocks a percentage equal to 100 minus your age. An investor following this rule will stash 80% of their capital in stocks when they’re 20, 70% when they’re 30, 60% when they’re 40, and so on. The idea here is that the older you get, the less risky your portfolio should be. To stick to this rule, you’ll need to rebalance your portfolio each year, a process that we’ll see later on.

In the last years, many professionals have started suggesting to their clients a reviewed version of the rule prescribing a higher share of stocks, namely 110 or even 120 minus the investor’s age. The reasons for that are mainly two: the current low interest rates environment, which led to low bond yields, and the lengthening of the average lifetime, which gives investors more time to recover from possible losses.

In any case, the final decision lies with you. You can use these rules as a starting point and then adjust your asset allocation based on your risk appetite and investment horizon.

Pick your baskets

Once you’ve defined your asset allocation, it’s time to choose the baskets of assets to invest in. Let’s say you’ve selected an 80% equities, 20% bonds allocation. Should the equity share be made up of US stocks, European stocks, or stocks from all over the world? And what about bonds? There are a ton of funds replicating stock and bond indices from any country and sector out there. Which ones should you pick?

Well, that’s ultimately your decision, but if you’re not sure about which stock or bond baskets to buy, the answer is fairly simple: go for the most diversified ones. As for stocks and corporate bonds, make sure the indices you pick include companies from different regions and industries; as to government bonds, they should be diversified both in terms of country and maturity.

The easiest and most cost-efficient way to reach the highest degree of diversification is to buy ETFs replicating world indices like the MSCI World, which tracks around 1,600 of the world’s largest corporations.

Find the best ETF

All right, here we are. You’ve defined your asset allocation and chosen the indices you want to invest in, so you open an account at a broker and browse the offered ETFs to find those that track them. At this point though, you might find more than one fund mirroring the same index. For example, there are at least 12 ETFs tracking the MSCI World out there. So how do you pick the best one? You can optimize your search by paying attention to a number of features of the fund. Let’s take a look at them.

Fund size

The bigger the fund, the less likely it is to be liquidated. A good rule of thumb is to prefer funds with more than €100 M in assets under management (AUM). Larger ETFs benefit from higher economies of scale, which translates into fewer fees for you. Moreover, larger funds tend to be traded more, so they’ll be more liquid and you’ll be able to buy them at a lower spread and sell them more quickly.

Fund age

A longer track record helps you better evaluate an ETF. Beware of funds old less than a year, as they bear a higher risk of being liquidated.

Currency risk hedging

If the fund includes assets denominated in a different currency than the one in use in your country of residence, you’ll incur currency risk. For example, if you live in Europe and you invest in a world index ETF allocating 60% of its assets to US stocks, 60% of your investment will be affected – either positively or negatively – by the EUR/USD exchange rate. While studies show that currency risk has little impact on equity returns over the long run, it can significantly affect short-term investments in stocks and investments in bonds. Some funds hedge currency risk and some don’t. Therefore, always pay attention to the fund’s hedging policy to make sure you’re not running any unwanted currency risk. The currency in which the fund is denominated has no impact on your currency risk.

Replication method

ETFs can replicate the underlying index in different ways, the most common ones being full replication, sampling and synthetic replication:

- Full replication: the ETF owns all the securities in the index in the same relative amounts shown by the index. Indices with numerous or illiquid stocks can be more difficult to fully replicate.

- Sampling: the ETF holds only a selection of the most important and liquid securities in the index. Sampling solves the problem above and tends to decrease management costs, but can lead to a higher tracking error.

- Synthetic replication: the ETF replicates the index by using a financial derivative (a swap). Synthetic replication is generally used to track niche markets, commodities or money markets. Funds like these tend to have some level of counterparty risk because they don’t own the underlying securities.

To summarize: the less risky method is full replication, followed by sampling and synthetic replication.

Distribution policy

ETFs can either distribute dividends on a regular basis or reinvest them in the fund automatically. Here the choice depends on your goal: if you want a steady income from your capital, then go for the first, otherwise, the second saves you time and transactions.

Fees

All the rest being equal, you’ll probably look for the cheapest fund. You can find it by looking at the Total Expense Ratio (TER), also referred to as the Ongoing Charge Figure (OCF). This is an approximate measure of the annual expenses the ETF will generate, expressed as a percentage of your investment. Watch out though: the TER only takes into account costs charged by the ETF manager, without including taxes nor fees charged by the broker. With BUX, you can trade ETFs without paying brokerage fees, which takes away part of the headache. Discover how.

Last recommendation before you tap “buy”: to be positively sure the ETF you’re about to purchase is really the one you think it is — and not another one replicating the same index with different features, always look its ISIN number (a 12-character alpha-numerical code that uniquely identifies a security) up on the Internet and read carefully its KIID, a document with all the information about the product which your broker has to provide you.

Rebalance your portfolio

After building your portfolio, you’ll need to monitor it. As a matter of fact, if one asset class grows in value more than the others over time, their relative weights will change, drifting away from your initial asset allocation and altering your portfolio’s risk/return profile.

During good times, for example, stocks tend to grow more than bonds in value. Therefore, at the end of a bull-market year, equities will probably be overrepresented in your portfolio, which will increase its risk above the level intended with your initial asset allocation.

Meanwhile, as previously mentioned, your acceptable risk level will probably decrease over time instead: as you grow older, you might want to trade some expected returns for some peace of mind (i.e.: reduce your stocks share to increase your bonds share).

To solve these two issues, a good practice is to analyse your portfolio once or twice a year to determine whether relative weights have changed, and rebalance them if needed in order to reach your new desired asset allocation.

You can do this by either buying more of the underrepresented asset class(es) in your portfolio — therefore injecting new capital in it, or by selling part of the overrepresented asset class to buy some of the others. Bear in mind that, in the second case, you could incur capital gain taxation depending on your country of residence.

As an example, let’s say you’re thirty years old and you start investing according to the 100 – age rule of thumb. At the moment of investing, you choose a 70% stocks, 30% bonds asset allocation. After one year, you take a look at your portfolio and realise equity grew to represent 72% of it, while now you would rather have a 69% stocks, 31% bonds mix (this is your new desired asset allocation). To achieve it, you’ll simply need to sell 3% of your portfolio’s value in stocks and buy bonds with that money. In alternative, you can buy additional bonds to dilute the equity share down to the desired percentage.

ETF investing strategies

The guide to building an ETF portfolio proposed in the previous sections assumes that you will buy and sell securities with the sole aim of putting in place your optimal asset allocation, without trying to time the market.

This is known as a buy-and-hold strategy, the simplest and most effective to invest in the long run. However, it is not the only one you can pursue. Investment strategies can be divided into 3 groups: buy-and-hold, market-timing, or a combination of the two. Let’s take a look at them.

Buy and hold

As said, this is the simplest and most effective strategy in the long run. You select an asset allocation that maximises your expected return given your chosen level of risk, you buy the necessary securities, and you stick with them for the whole duration of the investment independently on the ups and downs of the markets. You only sell securities when rebalancing and to liquidate your investment at the end.

This passive strategy is built on the assumption (based on historical evidence) that, in the long run, global stock markets tend to go up. The main factors driving this tendency are population growth, which increases the demand for goods and services, and technological innovation, which makes companies more productive. In the long run, the combination of these two forces tends to increase company profits and valuations accordingly.

Therefore, following this assumption, if you hold a diversified stock portfolio long enough you should end up with a profit. This makes buy-and-hold an effective strategy in the long term, even though it doesn’t ensure that it will work on shorter periods of time, over which returns can be significantly affected by volatility.

Also, its results rely heavily on the effect of compound interest: by reinvesting dividends from stocks and interest payments from bonds in the portfolio, you’ll increase your capital periodically, harvesting higher interests and dividends each time, in a virtuous cycle that will make your investment grow exponentially. But compound interest takes time to work, and that’s another reason why buy-and-hold is more effective in the long run.

There are two ways you can implement the buy-and-hold strategy. You either invest a lump sum or you distribute your purchases over time in smaller periodic installments — a method called unit-cost averaging. Both of these approaches have advantages and disadvantages.

- Lump-sum approach

If you have a sum at your disposal, you can decide to invest it all together. In theory, this would be the best approach, because it gives your entire capital more time to grow and maximises the compound interest your investment can generate.

On the other hand, imagine doing this at the tip of a market bubble. Seeing your portfolio crash right after you invest and not recover for years may be taxing on an emotional level. That’s why, even if you have a sum to invest all at once, you may decide to dilute your investment over time, sacrificing part of the potential returns for some more peace of mind and liquidity.

- Unit-cost averaging

Unit-cost averaging works like this: you invest the same amount of money in the same assets on a regular schedule (monthly or quarterly). When the price of the portfolio rises, your fixed sum will buy less of it, but when it falls, it will buy more. This way, you will accumulate more units of it at lower prices and fewer at higher ones, averaging out the cost of your assets.

This method minimises the downside risk of your investment, alleviating your worries when markets go down. In fact, on an emotional level, this is probably the best approach: when prices climb, you’ll be happy to see your portfolio grow, when they drop, you’ll see it as an opportunity to decrease the average cost of your investment. You can implement unit-cost averaging on BUX by setting up recurring bank transfers from your banking app.

As seen, theoretically, buy-and-hold is quite a simple strategy, but it requires a lot of willpower. You’ll have to stick to it no matter what happens on the stock market, which can turn out difficult in times of high uncertainty. When prices climb fast above all-time highs, you’ll be tempted to sell out of the dread of an imminent collapse. On the contrary, after a crash, you may feel the fear of missing out on a good opportunity to invest more. A unit-cost averaging approach can help you keep your discipline throughout the investment process, but it will do it at a cost over the potential returns of investing a lump sum.

Market timing

Market timing includes a broad range of strategies with one thing in common: the investor tries to predict future price movements and buys or sells securities accordingly.

These strategies involve active investment and are generally applied in the short run by setting rules that prescribe when to buy and sell according to specific signals, be them technical (related to price movements) or fundamental (hints that an asset is possibly momentarily under- or overvalued).

All the countless market-timing strategies out there rely on the assumption that markets can be predicted based on past data, even though financial theory rejects this hypothesis, stating that, in an efficient market, current prices already reflect all past information, so past data can’t say anything about the future.

Of course, in reality, markets are not always efficient, leaving room for some of these strategies to occasionally work in the short run, given one has superior prediction methods. However, there is evidence that they don’t beat buy-and-hold strategies over the long term in most cases. Therefore, unless you’re a seasoned professional investor with sophisticated tools to make market predictions, you’ll probably achieve better results by sticking to a buy-and-hold approach.

Combining the two

If you want to enjoy some active investing without risking deviating too much from the results that a passive strategy can generate, you could opt for a core-satellite approach, which is a combination of buy-and-hold and market-timing.

This method consists in dedicating the core of your portfolio (usually around 80% of it) to a long-term buy-and-hold strategy while using the rest of it (the satellite part) to try and chase higher expected returns by attempting to seize momentary occasions in the short term.

The satellite section of such a portfolio can also be used to achieve greater diversification than the core asset allocation would allow, for example by investing in peripheral markets or niche sectors with high growth potential but high risk.

Whichever approach you choose, BUX offers you a selection of ETFs suitable for any investment strategy, allowing you to trade them without commission. Take a look at them here.

ETCs on BUX

ETC stands for Exchange-traded commodities. ETCs are securities that are traded on stock exchanges, and their value is based on the price of a specific commodity. ETCs are designed to track the performance of a particular commodity, and they provide investors with a convenient way to gain exposure to the commodity markets.

What is the difference between ETFs and ETCs?

ETFs are investment funds that are traded on an exchange like a stock. They are designed to track the performance of a particular index, sector, or asset class, and their holdings can include stocks, bonds, and other securities. ETFs are often used by investors to gain exposure to a diversified portfolio of assets or to target specific investment themes or strategies.

ETCs, on the other hand, are designed to track the performance of individual commodities or baskets of commodities, such as precious metals, energy, or agricultural products.The ETCs offered by BUX consist of gold, silver, platinum and palladium. Investors in ETCs are generally seeking to profit from changes in commodity prices.

Why invest in ETCs?

Adding ETCs to a portfolio can help to diversify your portfolio across different asset classes. ETCs have lower correlation with traditional stocks. By investing in assets that are less correlated with traditional stock investments, you create a more diversified portfolio.

Additionally, some ETCs track the prices of precious metals like gold and silver, which are often seen as a hedge against inflation. Having ETCs in a portfolio can help to protect the portfolio from the negative effects of inflation.

What to keep in mind when choosing an ETC

- Commodity type: Determine the type of commodity you want to invest in. The ETCs offered by BUX make it possible to invest in gold, silver, platinum and palladium.

- Tracking method: Check the tracking method used by the ETC to ensure it matches your investment goals. Physical ETCs hold physical commodities, while synthetic ETCs use financial derivatives to track the price of the underlying commodity. For now BUX is only offering physically backed commodities.

- Volatility: Commodities prices are generally more volatile than other asset classes, making investments riskier than other investments. Prices of precious metals, industrial metals and other commodities are generally more volatile than prices in other asset classes. The less liquid a commodity or precious metal the more volatile it can be.

Our ETCs

- Xetra-Gold ETC

- Invesco Physical Gold ETC

- Xtrackers Physical Gold ETC

- WisdomTree Physical Silver ETC

- Xtrackers Physical Silver ETC

- WisdomTree Physical Platinum ETC

- WisdomTree Physical Palladium ETC

Our ETFs